Prelude

I do want to preface this by saying that while everything in this topic is what I personally have observed, read about, and practiced with my own fungus growing ants, it isn't necessarily 100% true. Nothing says that my experiences with my colonies will 100% reflect others' experiences, however this is meant to serve as a guide to how I've had such success with these ants and to clear up any misconceptions that may be floating around about them.

This topic will be covering the main range of fungus growing ants that people in the US would expect to keep; Atta, Acromyrmex, and Trachymyrmex.

Before we start, I do want to link my two main leafcutter journals, my Atta mexicana and Acromyrmex versicolor, as well as the Antkeeping & Ethology Discord server and my website, arthropodantics.com.

The Golden Rule

With that out of the way, let's start with what I would consider the golden rule when it comes to these species: NEVER HEAT FUNGUS GROWERS. I've seen this done too many times and it needs to be put out there that fungus growing ants do horribly in too hot of temperatures. I've found that temperatures over 85f are lethal to the fungus, and more than even a few minutes at these temperatures can cause fungus to die at an irreversible rate. Now, this may be hard to believe considering that species like Acromyrmex versicolor and Atta mexicana live in the desert, where it can reach well over 110f, but this same statement holds true for them. In the wild their nests are constructed in a specific way to allow for ventilation into the lower chambers to control temperature, and the nests themselves are several feet underground to insulate the fungus from the summer sun. With Atta especially, too warm of temperatures can not only kill fungus but also cause the workers to stop foraging entirely, creating a snowball effect. Generally an ambient heat that is less than 85f is fine, however anything more than that or any direct heat is almost always a bad idea.

Leafcutter Setup Tips

The next thing that people should know is what setups are suitable for leafcutters, and for many the answer may be more simple than expected. One further rule I'll add is to never use a test tube with fungus growers. As we all know cotton balls just love to mold over, and this mold growth is a death sentence for any fungus that may have been started in the test tube. Instead an ideal setup is a deli cup (I suggest <4oz in general, although >3oz for Atta) with a base of an absorbent material, such as Plaster of Paris, Ultracal 30, or Hydrostone. This base layer only needs to be around 1-2cm deep, and can be hydrated by simply opening the lid of the setup and dripping water directly onto the base. Avoid getting water on the fungus itself if possible. Another setup that works wonderfully for semiclaustral fungus growers (everything except Atta) is Ray Mendez' hydrostone petri dish founding formicarium. This video by Miles Maxcer at The Ant Network details how to build one: https://youtu.be/iceahERV8DU. This setup was used not by myself but another keeper in Arizona for Acromyrmex versicolor queens, and the ability to add an outworld to the setup increased their success rate to near 100%.

It just shows that a proper setup, diet, and conditions are all you need to be successful with these species. Do your research!

Once the colonies outgrow their founding formicaria, the options do increase a bit, however the basic principle of a layer of an absorbent material at the bottom will stay consistent. You can use any shape of container with any rigid material and a lid for a nest, so get creative! You also may want to introduce a third container, a trash chamber. This can just be a bare container hooked up to the nest, and you can teach the colony to put their trash in it by manually moving their trash into it from wherever they were previously placing it. They'll get the hint and start putting all trash in this designated chamber.

In addition to the possible setups, our nests over at https://www.arthropodantics.com/ were designed with leafcutter ants, specifically Acromyrmex versicolor, in mind. They're a perfect option for genera like Trachymyrmex and Acromyrmex, and may even be suitable for small Atta colonies. Check them out!

General Important Info

Here's a few more things to keep in mind when considering leafcutter ant care.

1: A varied diet is important. Even if you offer their favorite food constantly, the ants will eventually refuse it. This is a natural instinct that they have in order to not completely wipe out one species of plant in their area in the wild.

2: Always overestimate the food intake (if you want fast growth). These ants can process a LOT of plants, so don't hold back!

3: Fungus doesn't live forever. Don't be concerned if you see fungus dying, it's normal! So long as the colony is still feeding their fungus, and as long as the fungus isn't dying at a rate faster than the new fungus is growing, then everything is fine.

4: The sooner you get your queens after a flight, the better chances are that they still have a fungus pellet. It's worth it to go out to areas where these ants are present when they're likely to fly, as getting queens before they start digging is the best way to ensure they still have fungus.

With the general information out of the way, I'd like to delve into some specifics for each genus/species in question.

Trachymyrmex: They Cut Leaves!

I'm going to start with Trachymyrmex, as there is quite a lot of misconceptions revolving around this genus that I'd like to clear up. Most people likely hear that Trachymyrmex spp, are not "leafcutter ants", and assume that because of this label they use the other lower-attine diet, such as caterpillar frass. In truth, the term "leafcutter ant" is assigned to the clade of fungus growers consisting of Acromyrmex, Atta, and Amoimyrmex. The reason why genera like Trachymyrmex, Paratrachymyrmex, Mycetomoellerius, etc. are not part of this clade is not because they don't cut leaves, but instead because they are not polymorphic. Despite the designation as not being part of the "leafcutter ant" clade, they are still ants who cut leaves. Being a higher attine, much of their natural diet still consists of fresh plant material. Just in case you aren't convinced, here's some evidence:

FC user Mdrogun's T. septentrionalis journal: https://www.formicul...septentrionalis

and some of his videos showcasing this behavior:

Photos and a video from FC user Aaron567 of wild Trachymyrmex in his area:

My personal colony:

Other's posts:

BugGuide post from Maryland: https://bugguide.net...w/493276/bgpage

iNaturalist observation from Maryland: https://www.inatural...ations/48877321

And this isn't just T. septentrionalis!

Here's an iNat observation from AZ, of what's likely T. desertorum: https://www.inatural...ations/30592521

T. desertorum also is regarded with "Foragers have been observed to collect green leaflets and fresh flower petals"

So while yes, Trachymyrmex are not a member of the "leafcutter ant" clade, they are still higher attines. Stop saying their diet is mostly caterpillar frass, it's not true.

With that out of the way, here's a bit of extra info of various foods I've had success with:

Steel Cut Oats (their favorite)

Rose Petals

Iceberg and Romaine Lettuce

Oxalis spp. leaves

Mesquite spp. leaves

Oak Leaves

Another thing to note with most Trachymyrmex species, especially septentrionalis, is that they appear to require a diapause of some sort. Typically in the winter you'll see them disassembling and discarding large volumes of their fungus, and this is a sign that they're ready to go into diapause. To do this, simply reduce the temperature to something around 50f. Typically a fridge is not necessary, but a well insulated garage or just a cool room is enough. You can also use a wine cooler with more easily preset temperatures to make it not as cold as a typical fridge. Typically only around 2 months of diapause is required. It's possible that they're able to not diapause at all, however the process appears to be beneficial and possibly tied to some kind of biological clock. However until they start disassembling their fungus, you can care for them as normal. Only once they do this is it time to diapause them.

With Trachymyrmex out of the way, let's move on!

Acromyrmex (specifically A. versicolor)

This genus, and more specifically this species, has troubled antkeepers in the southwest for years now. However, with my personal experiences this species isn't too difficult, and while I'd consider them the most difficult of the 3 genera in this post, they're certainly far from impossible. As mentioned before, founding for this species almost entirely relies in a good setup. Getting a queen with a fungus pellet that survives in general is a game of luck, but so long as you get that and put her in a suitable setup it should be clean sailing from there. Acromyrmex versicolor queens with an outworld are almost like fully claustral queens, as A. versicolor tend to take, and even prefer dried foods. In the wild, colonies will gather large collections of plants around their nest entrances to allow them to dry out, before bringing them into the nest.

Here's some pictures from a local colony here in Mesa:

This also ties into colony founding, and really pushes the importance of an outworld. If the typical deli cup founding nest is used, food will remain wet because of the humidity in the chamber, and this can discourage queens from eating it. Instead in an outworld the food will dry out, and the founding queens can just come out and grab a piece whenever they need. Using a method similar to this you can expect that so long as queens have a fungus pellet, they will be almost guaranteed to succeed. You can also boost failed groups with the fungus from successful groups and get a success rate of almost 100%.

Founding with multiple queens together also increases the success rate, however it should be noted that most A. versicolor populations will seemingly not stay polygynous long-term. Ray Mendez observed that in Arizona, only the A. versicolor populations in and around the Tucson area are polygynous long-term, although this could use some more testing, especially outside of AZ.

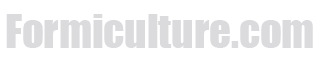

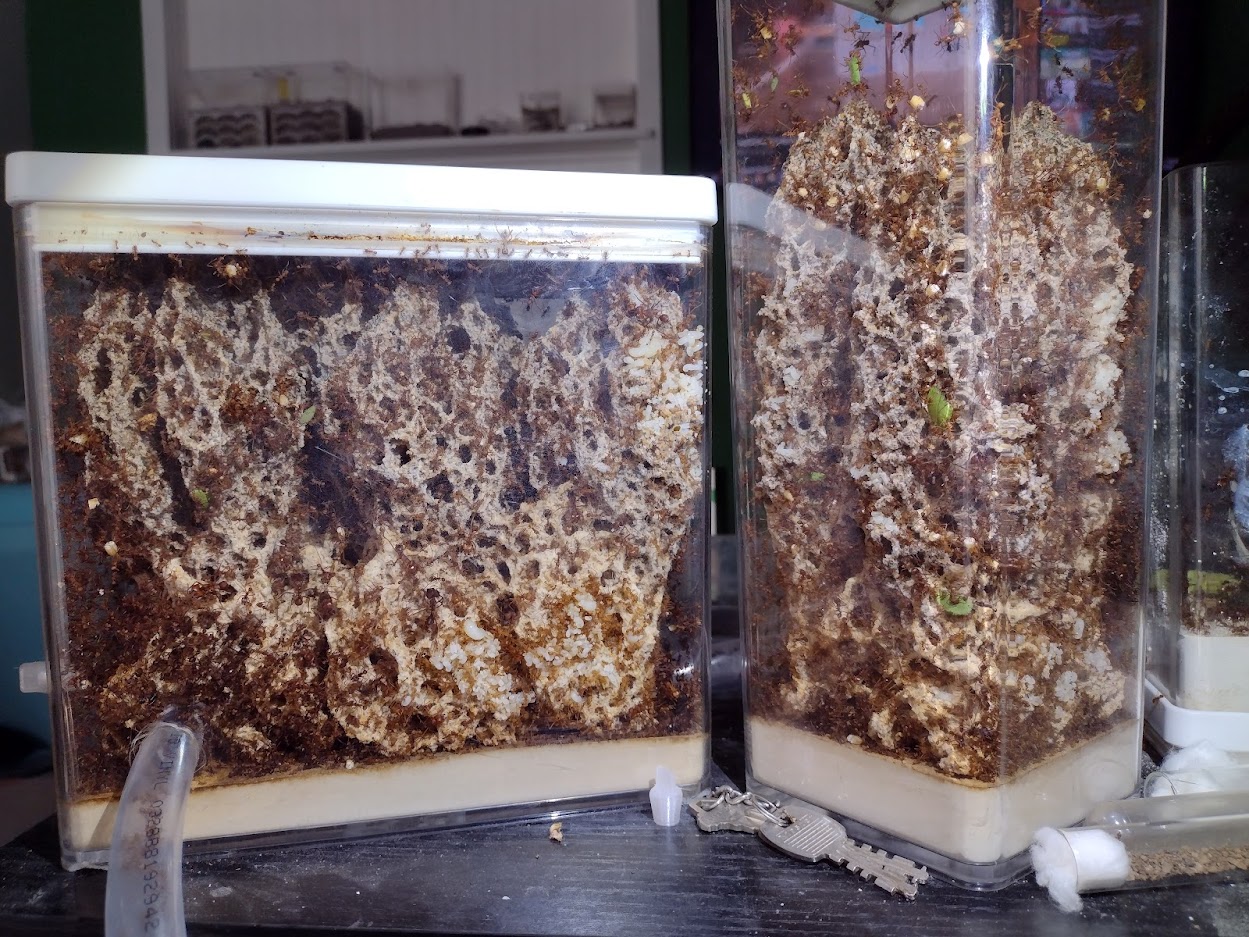

Post-founding care is relatively similar, basically just give them plants that they like and keep them at an appropriate temperature and they'll do just fine. One thing to note is that once they outgrow their founding setup, a setup with a lower ceiling is ideal, since they prefer to hang their gardens from the top of the setup. Just check out my colony doing this:

Now for foods that I've had success with:

Texas Sage flowers (their favorite)

Clovers (dried)

Mesquite spp. leaves

Steel-cut oats

Palo Verde Leaves

Mesquite flowers

Palo Verde Flowers

A. versicolor flight info:

Typically during the wet/monsoon season in the Southwest, typically from July to early October.

Flights will be first thing in the morning after a heavy rainstorm. (around 5am)

Queens will mate on the ground, so you can throw queens and males together and they will mate.

Flights are too late to blacklight, it will be far too bright out, however the alates are easy to find, and often even make giant piles on the ground to mate.

Atta

Some of you may be surprised when I say this, but Atta are almost certainly the easiest genus on this list. They are absolutely the easiest to deal with founding, as they are fully claustral. Just stick them in a proper deli cup setup and come back 6 weeks later to a nice chunk of fungus and 50-60 workers. This huge amount of nanitics is also a huge factor since they're able to process far more plant material after founding than the other genera. Once the deli cup starts to get cramped, a larger setup following the same principles is all they need. To move Atta, just use a rubber glove to protect yourself and pic up the entire fungus garden at once and move it to the new container. Once the colony gets too big to do this, invest in a modular setup, where you can simply attach new nesting space as needed.

All fungus growers, but Atta specifically have a great trait, which is the ability to easily limit their colony size. Since the queen lays based on the volume of fungus present, you can keep the food intake to a rate where the garden stays small, and the colony never grows. E. O. Wilson did this in his lab, and described it as a "bonsai" Atta colony. So yes, while Atta naturally get millions of workers, you can easily limit them to any size you want in captivity.

Their diet is also fairly easy, especially as the colony gets bigger. Smaller colonies will be more picky, since one bad food item could compromise the entire fungus garden, but as they get larger they will be less cautious and take in a much wider variety of food. As long as the food you offer is good, this can mean some pretty tremendous growth!

I have heard also that the hardest part about Atta is keeping a consistent humidity and temperature. With Atta mexicana this is not the case. They are extremely tolerant of a wide range of temperatures and humidity, and so long as you make sure they're not too hot (over 85f) and the setup has water, they'll be ok. These plaster leafcutter setups hold water for weeks at a time, so don't stress about watering them every single day. This may not be true for other tropical Atta species, however I'm sure they're not too much different than A. mexicana.

Lastly, let's go over some prime Atta food:

Oxalis spp. (O. stricta and related species)

Clovers

Mesquite spp. leaves

Oak Leaves

Roses

Steel-cut oats

Various other broad-leaves and flowers

Atta flight info:

A. mexicana fly in the early morning in the wet season.

In Mexico their flights typically start in June, but in the Sonoran Desert/AZ they don't fly until the monsoon season, which typically starts in July.

Their ideal amount of rainfall is around 1cm. If it rains too much more than that, they will wait a day before flying.

They fly earlier than Acromyrmex, beginning to take off while it's still dark (around 4am typically)

Atta texana fly at the same time of day, however earlier in the year.

Heat and humidity are the main triggers for texana, with a low in the 70s or higher being preferred. Typically a warm day after a heavy rain is a good time to look.

The bulk of flights are in April and May, however they may start as early as February in certain areas.

And that's just about everything I can think to include! I'll try to answer any specific questions if they pop up, but I really hope this guide will come in handy for people who are just starting to keep these species!

Edited by CheetoLord02, Yesterday, 11:50 AM.