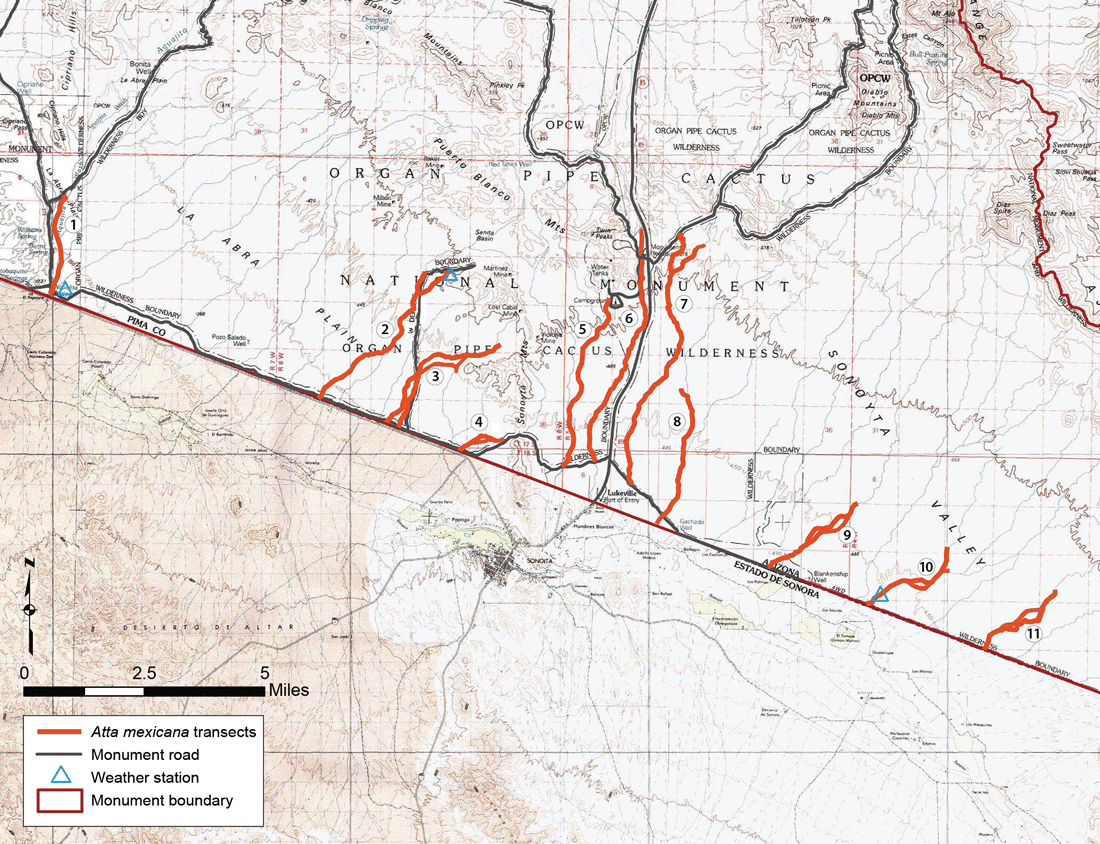

During a visit of the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in southern Arizona, myself and a colleague had set out to observe and document the population of Atta mexicana that has been reported and studied previously at this location. Following reports of wildlife damage in the area following the construction of the international border wall as well as the lack of natural rains in the last year, we were curious to see if we could find the species at all, let alone a way to check on the health of the overall population in the area. This trip was simply to serve as a simple observation of the colonies, and while we would be recording data, this is not intended to be an official scientific study and instead just a write-up of our findings.

Using the report from 2015-16 by Alex Mintzer as a rough guide, we followed his chart to transect 7, roughly 1 mile east of mile marker 78 along Arizona State Route 85.

We selected this transect specifically as it seemed to be easy to reach and was reported to have a healthy population of A. mexicana in the 2015-16 study (8 total colonies reported). Upon reaching the correct wash, we quickly spotted the first Atta mexicana worker and followed her back to her colony. The colony appeared to be small, and had a single nest entrance underneath a Mesquite tree. Behavior consisted of moving dead workers to a pile, as well as bringing in small amounts of plant matter. No more than 30 workers were seen out of the nest at one time, suggesting that the colony was no more than a year old, however 2-3 large foragers were spotted, being around 14-15mm in length. Observations of captive colonies suggest that workers of this size can be produced in the first year, so the theory of this colony being young stands.

After the first colony was located, following the wash south we continued to spot colonies of Atta mexicana. Curiously, the smaller washes closer to the highway than transect 7 had a number of Acromyrmex versicolor colonies, yet no Atta mexicana. This was a direct contrast to transect 7, as the only leaf-cutting ants present were Atta mexicana. Most of the colonies were identified based on a large collection of creosote leaves surrounding the nest entrance.

A number of colonies were observed to have trails that stretched for at least 50 feet, many of which were directed up and out of the wash and into the surrounding desert scrub. Trails seemed to follow the upper border of the wash before proceeding down into the nest entrance, which was almost always located on the side wall of the wash. One larger colony had 4 nest entrances located along a roughly 30 foot stretch of the wash, and workers were brought between entrances to test aggression and confirm that all 4 entrances were in fact the same colony. The 2015-16 study of this transect reported 8 colonies within a 1 mile stretch, however we located roughly 15 in the same distance, although admittedly we lost count after 8. Either way, we can confirm that the population in this transect is growing and even thriving despite the lack of significant rains in the area.

Moving out of the transect 7 wash, we wished to observe the Atta mexicana in the border town of Lukeville, since video footage by Alex Mintzer had confirmed the species to be present here. The Gringo Pass Motel on the east side of the town had a large number of colonies in the surrounding property and even in the parking lot itself. One colony located near the street at (31.881566, -112.815610) displayed very interesting behavior. Their nest structure consisted of several massive mounds, and this exact colony had been featured in the previously mentioned video. However, their behavior indicated that despite the huge mound, this colony was likely not healthy. The entire mound was covered in dead fungus, several inches thick in most spots, and there were no trails out or plant material being brought into the nest.

None of the other colonies observed had large piles of dead fungus nearby, and nearly all were actively bringing in plant material. It’s possible that due to this colony’s age the queen of the colony had died, and the remaining workers were simply killing off the rest of the colony since they had essentially lost any reason to continue developing the fungus and nest. This is just a theory, however this odd behavior unseen in any other colony should be addressed.

In the motel parking lot a number of large colonies were observed, one of which even had a series of 3 nest entrances over a 40+ foot area, and had a trail connecting them and climbing a nearby tree to collect its leaves. The trail appeared to be at least 60 feet in total length, however we were unable to determine how far up the tree the workers were travelling. We were also unable to identify the species of tree, however leaves were collected and offered to a captive Atta mexicana colony, and were readily accepted. The only other species of ants in the area were Novomessor cockerelli, Solenopsis xyloni, and Forelius mccooki, however the Atta outnumbered all three of those species in the number of colonies present.

Based on our observations, we can draw a few conclusions, but were ultimately left with more questions than answers. We can conclude that the Atta mexicana population located here in southern Arizona is thriving, and at the least in the two areas we observed the population seems to be growing. It also seems that despite the human influence in the area, specifically along the international border, the populations appeared to become healthier and more dense in the far southern portions of the preserve. Furthermore we were also able to more closely document their nesting preferences and foraging behaviors. In the preserve, away from human influence, they seemed to be restricted to specific washes, and seemed to nest exclusively on the sides of the washes. Their foraging also led them right along the outer ridges of the washes to collect the plants there. The flora tends to grow in a higher density along washes, so this foraging pattern makes sense. However, we still were left with a number of questions that we could only theorize about:

Why do only a specific number of washes contain A. mexicana, when all washes contain a higher abundance of flora than the surrounding desert? What prevents the Atta from spreading to these other nearby washes?

Why are the Atta in the preserve restricted to washes, however the Lukeville colonies are able to survive in a parking lot?

What is the relationship between Acromyrmex versicolor and Atta mexicana like at Organ Pipe? Why does neither species appear to occupy the same microhabitats as each other, and washes typically contain one of the two species, but not both?

Credits:

T. S. Boehmer (arthropodantics@gmail.com)

Jack Henderson (BroJack@SanMiguelHigh.org)

Alex Mintzer: Author of study used to locate colonies (amintzer@cypresscollege.edu)

Bonus video of various colonies observed: