The Experimental Process of Creating Multispecies Ant Colonies

WARNING: THIS PROCESS IS STILL EXTREMELY EXPERIMENTAL AND SHOULD NOT BE ATTEMPTED BY ANYBODY! UNTIL THE PROCESS IS FULLY FLESHED OUT, WE CANNOT GUARANTEE ANY INFORMATION PRESENTED HERE WILL BE ABLE TO BE REPLICATED CONSISTENTLY IN OTHER ATTEMPTS.

Note: This document and the information within this document is a compilation of work and research by an entire group of people. Credit is given at the end and throughout the document. Regardless of who posts this, the info here is compiled by all contributing members, who are linked at the end of the document.

This post is created as a result of requests for making public our current research and a desire to be more transparent with our processes as we develop them. None of this is final and information could change by the hour. This should not be treated as a guide and rather as a journal exploring the beginning of our personal experimentation.

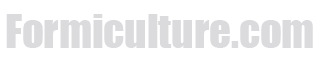

We began research in September 2020 upon the discovery of the works of Chilean antkeeper Robert Fuentalba Ojeda. A small group of experienced antkeepers decided to attempt a similar experiment with colonies of their own. Unfortunately Robert is very secretive about his methods, so we were essentially left to theorize on how the process worked. However, it is critical to give credit to Robert for all of his interesting work and giving us the inspiration and motivation to pursue this ourselves. Links to his work will be referenced at the bottom.

(Photo by Robert Fuentalba Ojeda)

We define a multispecies colony as a colony with two or more species cooperating, with egg-laying queens of all species cooperating without any aggression towards one another. Yes, colonies like these do appear to be possible, and they can be functional long-term.

We originally had a lead about using brood, specifically pupae, during founding, that swapping two species’ queens’ brood during founding would somehow translate their scent between each other or that the eclosed workers would still have ties to their mother queen. However, mostly due to the time of year we didn’t really have the resources to attempt this strategy for the time being. We will likely conduct experiments with this method later, however we cannot confirm if this works with our own experience. We have tried brood-boosting cross-species with some success, and Robert has also seemingly had success with this strategy, but until we are able to further experiment with it we are unable to confirm or deny whether or not this strategy is viable for sure, and we absolutely do not recommend anybody to try this. The most success we have had is giving other species brood to certain colonies, for example Myrmica being given Tetramorium immigrans brood, or Monomorium being given Tetramorium bicarinatum brood, however, although the brood was eclosed and the ants cooperated (trophallaxis occurred) this would not count as a “real” multispecies colony, and it does not always work. Trying to use brood to make a true multispecies colony (with two or more producing queens of different species) has not been fleshed out and may not even work. We absolutely need to test this further to verify its legitimacy.

Moving away from the brood-swapping method, the idea of using white vinegar to remove the scent of an ant was brought up. White vinegar is often used to neutralize the pheromone trails of ants, specifically pest ants in homes, and we used this logic to begin. Amatty76 was the first to try something, where he simply dunked a Formica subsericea queen in vinegar for roughly 15-20 seconds before adding her to a Camponotus pennsylvanicus colony that was fresh out of diapause (because he’s a chimp). Being in a diapause-like state, the Camponotus were unable to fully recognize the presence of the Formica queen. Over the next few minutes/hours, as the Camponotus were fully waking up from their diapause, the Formica queen had already gotten the scent of the Camponotus colony. The Formica queen was observed to be groomed by the Camponotus workers. Unfortunately, after around a week of the colony cooperating, the Camponotus pennsylvanicus queen died. He attempted to re-dunk and re-introduce the Formica queen to a new Camponotus colony, however the Camponotus killed the Formica queen before she was able to fully get their scent.

Moving forwards with this same strategy, several other attempts were done by various members. Cheeto attempted to add 3 Lasius brevicornis queens to a Camponotus chromaiodes colony after dunking the Lasius in vinegar. Both groups were fresh out of diapause. For a few days everything seemed to work, but later the Camponotus were observed killing a Lasius brevicornis queen. Notably, unlike the previous Formica x Camponotus attempt, the sleepy C. chromaiodes did appear to have a distaste for the Lasius queens, just were physically unable to do anything due to their diapause-like state. As soon as they were fully awake, they began to fight with the Lasius queens. This just proves that this strategy IS NOT flawless, and should only be attempted with extreme care by experienced keepers who are willing to risk queens and/or colonies.

Cheeto’s next attempt was far more successful. He did the same strategy, however with Camponotus castaneus and Pogonomyrmex occidentalis, each colony having one worker. The main notable difference is that neither colony had any aggression towards each other after dunking both the Pogonomyrmex queen and worker in vinegar. Both colonies had practically successfully merged into one, however being fresh out of diapause Cheeto was having issues with things like feeding. A bit of sunburst was consumed by the C. castaneus, but other than that there was little eating going on. Furthermore, neither colony had any brood due to a rough first season, so getting this multispecies colony to functionality would be difficult. To attempt to kickstart their development, brood of both Camponotus vicinus and Pogonomyrmex barbatus was added. Both were accepted with little issues.

(Photo Credit @Ants_AZ)

One issue did happen, though, where the P. occidentalis worker became aggressive for seemingly no reason, not towards the C. castaneus but rather at… seemingly nothing. However, the C. castaneus queen was not happy with the new little ball of rage, and bit the occidentalis worker, decapitating her in a single bite. Despite this, the P. occidentalis queen still has no issues with the Camponotus. It is thought that this is a result of them being newly introduced.

One thing to note is that at one point the C. castaneus queen was attempting to cover up a drop of sunburst in the tube, and when she ran out of material like seeds that were originally offered for the Pogonomyrmex, she simply picked up the Pogonomyrmex queen and attempted to place her in the sunburst. This did not invoke an aggressive response from the Pogonomyrmex, and the act of picking up the Pogonomyrmex queen was not done in aggression either. After walking away from the sunburst and back to the Camponotus, the C. castaneus queen once again picked up the Pogonomyrmex queen and attempted to place her in the sunburst drop. After seeing this, Cheeto cleaned up the sunburst drop and the Camponotus queen no longer attempted to move the Pogonomyrmex queen. This interaction would make it seem that by the manipulation of the scents and by the ants not being closely related species, each species doesn’t even recognize the other as being ants, and rather just something else that they don’t feel the need to attack. That is just a theory, though. Some similarly unrelated colonies may perform trophallaxis and groom each other, so this may not always be the case. Again, this process is still in its infancy and should not be attempted.

(Photo Credit @Ants_AZ)

Later, Anthony attempted a combination of Lasius cf. crypticus and Lasius brevicornis. The following is the steps he took for combining these two queens. The Lasius crypticus queen was sitting in diapause, and the Lasius brevicornis queen was in a test tube. Neither had brood. Anthony first prepared a dish of white vinegar, upon which he took out the Lasius crypticus queen from the fridge and dumped her into the dish of vinegar, submerging her for 10-20s. After removing her from the vinegar, the L. brevicornis queen was allowed to dry off before being introduced to the L. crypticus. The L. crypticus queen was asleep from diapause, the L. brevicornis queen was awake. The brevicornis queen then licked the L. crypticus queen and cleaned herself off in the tube. When the Lasius crypticus queen woke up, neither were aggressive toward one another. However, after a few minutes, although docile when beside each other, if they interacted via antennate they would bare mandibles and act aggressive toward one another.

Because of the apparent aggression between the two queens, Anthony needed something to calm the queens down. He gave them a drop of sunburst at the mouth of the tube, and the queens proceeded to prioritize food over fighting. The queens were so close to one another that they were in contact the entire time that they were eating. This definitely assisted in their eventual cooperation.

Soon after this, the queens could still be seen making the occasional aggressive gestures toward one another, namely the L. brevicornis queen. However, as time went on and they calmed down, the queens were able to settle. It’s important to note that the test tube setup nesting space was a bit smaller than most, so the queens were forced to be in a small space.

Theoretical issues with this colony may arise when workers emerge, considering that L. crypticus exhibit pleometrosis. This could mean that L. crypticus workers may recognize the L. brevicornis queen and kill her, or possibly even kill the L. crypticus queen, however only time will tell if this is the case.

As for certain variables with this, namely the species used, monogyny, and other similar factors, we have yet to extensively test if these play a huge role in the success of this project. Further testing will need to be done with a wider range of species, and more species than just two in a single colony.

We want to make it abundantly clear once again: this process is extremely experimental and not polished whatsoever. Until we figure out a surefire way to go about this without fail, we recommend NOBODY try to replicate what is shown in this topic. We simply want to be more transparent about this process so that it may be used in the future, possibly for a greater purpose than just the hobby.

As for the future of this thread: we want this thread to be the place where we can share our information as well as answer questions. Those who have helped with this will make update posts in a journal format.

References/Credit

Robert Fuentalba Ojeda is the one who first seemingly perfected this practice, and his photos are that which inspired us to pursue this.

The Antkeeping & Ethology Discord Server, where most of the experiments were coordinated, and where information was shared and theories crafted.

Original Participating/Contributing Members: Myself (Cheeto), Aaron, Madbiologist, Arman, AnthonyP163, Amatty, Otter, something, EchoMeter4, and others from the Discord.

Camponotus x Pogonomyrmex Photos by Ants_AZ on Instagram.

Edited by CheetoLord02, January 10 2021 - 7:53 PM.